On December 31st 2024, I decided that it was time to convert my scheme implementation to a CPS-based JIT compiler from an AST interpreter. The main reason for this was to make the creation of continuations mechanical. I would say that when implementing a language with call-with-current-continuation there are two “proper” ways to go about it:

Convert your program to some sort of bytecode that can run in a virtual machine. This makes implementing

call/cc somewhat trivial; capturing the current continuation is akin to saving the stack and current program

counter to be restored at a later time. With a bytecode virtual machine, this process can be made safe and efficient.

Convert you program to Continuation-Passing Style.

Converting to CPS explicitly and mechanically describes the continuations of your program. After this is done,

call/cc is as easy as implementing a builtin the clones the environment of the passed continuation and passing

it to the provided thunk.

I decided to go with CPS because I thought it would be a more interesting learning experience and it aligns

with my goal of making scheme-rs as fast as possible; CPS is an appropriate IR to perform analysis and

optimizations on, and thus seems like the right move to make scheme-rs as fast as possible.1

So to start, let’s do some crude estimates with our interpreted implementation of scheme. Our benchmarking

function will be the fibonacci function, and we will call it to calculate fib(10000):

(define (fib n) (define (iter a b count) (if (<= count 0) a (iter b (+ a b) (- count 1)))) (iter 0 1 n)) (fib 10000)

This is a pretty good target function to optimize because it sort of represents a maximally optimizable function: It’s pure, does math, iterative, and is just generally well known. So the success of most optimizations that we are going to implement have some sort of impact on this function, and that is especially the case for optimizations early on in the life of a compiler.

On the final interpreted version of scheme-rs, calling this function took 40 ms on average on my machine.

By way of comparison, Guile took 3 ms on average, so over 10x faster. Guile is probably the scheme

implementation installed on the most computers, so it seems like a fine enough comparison. We will be trying to

compete with that.

So I went away and implemented CPS. scheme-rs now took the AST, converted that into CPS, converted that into

LLVM SSA2, and then JIT compiled that. I ran my fib benchmarks:

fib 10000 time: [356.36 ms 357.57 ms 358.82 ms]

change: [+772.31% +778.10% +783.54%] (p = 0.00 < 0.05)

Performance has regressed.

Oh geez.

Yeah, I bet you thought this was a story about making scheme-rs super fast compared to other scheme implementations.

Nope! It’s a story about getting scheme-rs back into the same ballpark!

But boy did we get back to the same ballpark, through three optimizations.

Although I say three, the first is basically so important that I would consider it to be an effectively necessary part of the continuation-passing conversion algorithm, and it is:

CPS conversion algorithms typically produce a bunch of junk closures that seem pretty trivial to eliminate with

some amount of analysis. For example, here was the initial CPS output for the very simple (+ 1 2 3 4):

Scheme equivalent output:

(define (k3 arg k) (+ arg 4 k)) (define (k2 arg k) (+ arg 3 k)) (define (k1 arg k) (+ arg 2 k)) (k1 1 (lambda (arg) (k2 arg (lambda (arg) (k3 arg (halt))))))

compiling: TopLevelExpr {

body: Closure {

args: ClosureArgs {

args: [

%1288,

],

variadic: true,

continuation: None,

},

body: ReturnValues(

%1288,

),

val: %1287,

cexp: Closure {

args: ClosureArgs {

args: [

%1290,

],

variadic: false,

continuation: None,

},

body: Closure {

args: ClosureArgs {

args: [

%1294,

],

variadic: false,

continuation: None,

},

body: App(

%1294,

[

$+,

],

),

val: %1293,

cexp: Closure {

args: ClosureArgs {

args: [

%1291,

],

variadic: false,

continuation: None,

},

body: Closure {

args: ClosureArgs {

args: [

%1296,

],

variadic: false,

continuation: None,

},

body: Closure {

args: ClosureArgs {

args: [

%1298,

],

variadic: false,

continuation: None,

},

body: Closure {

args: ClosureArgs {

args: [

%1300,

],

variadic: false,

continuation: None,

},

body: Closure {

args: ClosureArgs {

args: [

%1302,

],

variadic: false,

continuation: None,

},

body: App(

%1291,

[

%1296,

%1298,

%1300,

%1302,

%1290,

],

),

val: %1301,

cexp: Closure {

args: ClosureArgs {

args: [

%1304,

],

variadic: false,

continuation: None,

},

body: App(

%1304,

[

$4,

],

),

val: %1303,

cexp: App(

%1303,

[

%1301,

],

)

}

},

val: %1299,

cexp: Closure {

args: ClosureArgs {

args: [

%1306,

],

variadic: false,

continuation: None,

},

body: App(

%1306,

[

$3,

],

),

val: %1305,

cexp: App(

%1305,

[

%1299,

],

)

}

},

val: %1297,

cexp: Closure {

args: ClosureArgs {

args: [

%1308,

],

variadic: false,

continuation: None,

},

body: App(

%1308,

[

$2,

],

),

val: %1307,

cexp: App(

%1307,

[

%1297,

],

)

}

},

val: %1295,

cexp: Closure {

args: ClosureArgs {

args: [

%1310,

],

variadic: false,

continuation: None,

},

body: App(

%1310,

[

$1,

],

),

val: %1309,

cexp: App(

%1309,

[

%1295,

],

)

}

},

val: %1292,

cexp: App(

%1293,

[

%1292,

],

)

}

},

val: %1289,

cexp: App(

%1289,

[

%1287,

],

)

}

},

}

The problem with this output is that there are a lot of useless functions. That’s bad, those all have overhead.

From what I can tell, there are two ways to make good CPS: make the output good from the start, or run optimization passes on output until it’s good3.

I went with a relatively simple beta reduction step. This is effectively function inlining. We replace function calls with the output of a function’s body with the arguments of the function call substituted into the body. If after doing this some number of times the function is no longer called, we can eliminate it completely. It’s called beta reduction because that is what function application is called in the lambda calculus4.

There are so many ways to do this, but we will use an extremely simple heuristic: If a function is only used once in its continuation expression and is non-recursive, replace that use with a beta-reduction:

impl Cps { pub(super) fn reduce(self) -> Self { // Perform beta reduction twice. This seems like the sweet spot for now self.beta_reduction(&mut HashMap::default()) .beta_reduction(&mut HashMap::default()) } /// Beta-reduction optimization step. This function replaces applications to /// functions with the body of the function with arguments substituted. /// /// Our initial heuristic is rather simple: if a function is non-recursive and /// is applied to exactly once in its continuation expression, its body is /// substituted for the application. /// /// The uses analysis cache is absolutely demolished and dangerous to use by /// the end of this function. fn beta_reduction(self, uses_cache: &mut HashMap<Local, HashMap<Local, usize>>) -> Self { match self { Cps::PrimOp(prim_op, values, result, cexp) => Cps::PrimOp( prim_op, values, result, Box::new(cexp.beta_reduction(uses_cache)), ), Cps::If(cond, success, failure) => Cps::If( cond, Box::new(success.beta_reduction(uses_cache)), Box::new(failure.beta_reduction(uses_cache)), ), Cps::Closure { args, body, val, cexp, debug, } => { let body = body.beta_reduction(uses_cache); let mut cexp = cexp.beta_reduction(uses_cache); let is_recursive = body.uses(uses_cache).contains_key(&val); let uses = cexp.uses(uses_cache).get(&val).copied().unwrap_or(0); // TODO: When we get more list primops, allow for variadic substitutions if !args.variadic && !is_recursive && uses == 1 { let reduced = cexp.reduce_function(val, &args, &body, uses_cache); if reduced { uses_cache.remove(&val); return cexp; } } Cps::Closure { args, body: Box::new(body), val, cexp: Box::new(cexp), debug, } } cexp => cexp, } } fn reduce_function( &mut self, func: Local, args: &ClosureArgs, func_body: &Cps, uses_cache: &mut HashMap<Local, HashMap<Local, usize>>, ) -> bool { let new = match self { Cps::PrimOp(_, _, _, cexp) => { return cexp.reduce_function(func, args, func_body, uses_cache) } Cps::If(_, succ, fail) => { return succ.reduce_function(func, args, func_body, uses_cache) || fail.reduce_function(func, args, func_body, uses_cache) } Cps::Closure { val, body, cexp, .. } => { let reduced = body.reduce_function(func, args, func_body, uses_cache) || cexp.reduce_function(func, args, func_body, uses_cache); if reduced { uses_cache.remove(val); } return reduced; } Cps::App(Value::Var(Var::Local(operator)), applied, _) if *operator == func => { let substitutions: HashMap<_, _> = args .to_vec() .into_iter() .zip(applied.iter().cloned()) .collect(); let mut body = func_body.clone(); body.substitute(&substitutions); body } Cps::App(_, _, _) | Cps::Forward(_, _) | Cps::Halt(_) => return false, }; *self = new; true } }

This optimization is enormously effective, we gain all of our performance losses back instantly:

Running benches/fib.rs (target/release/deps/fib-08cbbdc89a1c73d1)

fib 10000 time: [42.418 ms 43.993 ms 45.544 ms]

change: [-88.135% -87.697% -87.241%] (p = 0.00 < 0.05)

Performance has improved.

Now our output for (+ 1 2 3 4) isn’t as crazy:

compiling: TopLevelExpr {

body: Closure {

args: ClosureArgs {

args: [

%2142,

],

variadic: true,

continuation: None,

},

body: Halt(

%2142,

),

val: %2141,

cexp: App(

$+,

[

$1,

$2,

$3,

$4,

%2141,

],

),

},

}

I should note that my original implementation of this optimization was subtly buggy; I’ve since replaced it with a more correct version that you see here.

As stated earlier, this is by far the most effective optimization. In a couple hundred lines of code we re-gained all of the lost perf for our CPS conversion. Let’s add a couple more optimizations:

There are a bunch of functions that are more well understood than others, whether by being understood better in the context of our runtime system (such as list operations) or by simply being more common and well studied (such as the arithmetic functions). It is important to be able to recognize invocations of these functions so that we can optimize their uses.

The primitive operators that are in our fib function are the arithmetic + - * / and comparison

> < >= <= = operators. Therefore, we will be optimizing those. If we give these operators dedicated

runtime functions as opposed to being simple scheme or rust functions, we should be able to get some

performance gains.

First, we need to map expressions to primitive operators. We do this by checking if the function pointer for a global variable is equal to a known function:

impl Expression { pub fn to_primop(&self) -> Option<PrimOp> { use crate::{ num::{ add_builtin_wrapper, div_builtin_wrapper, equal_builtin_wrapper, greater_builtin_wrapper, greater_equal_builtin_wrapper, lesser_builtin_wrapper, lesser_equal_builtin_wrapper, mul_builtin_wrapper, sub_builtin_wrapper, }, proc::{Closure, FuncPtr::Bridge}, }; if let Expression::Var(Var::Global(global)) = self { let val = global.value_ref().read().clone(); let val: Gc<Closure> = val.try_into().ok()?; let val_read = val.read(); match val_read.func { Bridge(ptr) if ptr == add_builtin_wrapper => Some(PrimOp::Add), Bridge(ptr) if ptr == sub_builtin_wrapper => Some(PrimOp::Sub), Bridge(ptr) if ptr == mul_builtin_wrapper => Some(PrimOp::Mul), Bridge(ptr) if ptr == div_builtin_wrapper => Some(PrimOp::Div), Bridge(ptr) if ptr == equal_builtin_wrapper => Some(PrimOp::Equal), Bridge(ptr) if ptr == greater_builtin_wrapper => Some(PrimOp::Greater), Bridge(ptr) if ptr == greater_equal_builtin_wrapper => Some(PrimOp::GreaterEqual), Bridge(ptr) if ptr == lesser_builtin_wrapper => Some(PrimOp::Lesser), Bridge(ptr) if ptr == lesser_equal_builtin_wrapper => Some(PrimOp::LesserEqual), _ => None, } } else { None } } }

When compiling the AST to a continuation expression, we can check to see if it’s a primitive operator, and compile it separately:

fn compile_apply( operator: &Expression, args: &[Expression], call_site_id: CallSiteId, mut meta_cont: Box<dyn FnMut(Value) -> Cps + '_>, ) -> Cps { let k1 = Local::gensym(); let k2 = Local::gensym(); let k3 = Local::gensym(); let k4 = Local::gensym(); Cps::Closure { args: ClosureArgs::new(vec![k2], false, None), body: Box::new(if let Some(primop) = operator.to_primop() { compile_primop(Value::from(k2), primop, Vec::new(), args) } else { // Compile normally... }), val: k1, cexp: Box::new(meta_cont(Value::from(k1))), debug: None, } } fn compile_primop( cont: Value, primop: PrimOp, mut collected_args: Vec<Value>, remaining_args: &[Expression], ) -> Cps { let (arg, tail) = match remaining_args { [] => { let val = Local::gensym(); return Cps::PrimOp( primop, collected_args, val, Box::new(Cps::App(cont, vec![Value::from(val)])), ); } [arg, tail @ ..] => (arg, tail), }; let k1 = Local::gensym(); let k2 = Local::gensym(); Cps::Closure { args: ClosureArgs::new(vec![k2], false, None), body: Box::new({ collected_args.push(Value::from(k2)); compile_primop(cont, primop, collected_args, tail) }), val: k1, cexp: Box::new(arg.compile(Box::new(|result| Cps::App(result, vec![Value::from(k1)])))), } }

It’s great to have more information like this for a multitude of optimizations, but even just avoiding calling a user function and calling a known function is quite an effective optimization, as it avoids using a continuation expression:

Running benches/fib.rs (target/release/deps/fib-08cbbdc89a1c73d1)

fib 10000 time: [16.564 ms 18.038 ms 19.554 ms]

change: [-62.996% -58.997% -55.266%] (p = 0.00 < 0.05)

Performance has improved.

The last major optimization I wanted to do before moving on with feature development was to fix the value type for scheme-rs. Originally, it was a giant enum that cells would refer to via a reference counted smart pointer with interior mutability.

This was pretty bad. The reason is that using an enum did not give me enough control over the final representation of the value type. If I had released scheme-rs to the public, people would start matching on the enumeration, and I would have to provide the enumeration as a stable interface. It would be impossible to change at that point. So, if I was going to change the representation of the value type, I had to do it before it was released.

I decided to go with a tagged pointer representation of the value type, which is fairly standard. I settled on a four-bit tag to give myself 16 possible values for the tag.

This is fairly large. Most implementations use a three-bit tag. By increasing the tag size, you are increasing the alignment requirement for your allocated pointers, which can increase memory fragmentation.

The nice thing is that I can change this! I have now made my Value type an opaque struct that the API consumer cannot use directly, but must inspect via methods. If wish to change the representation in the future, I can, in so far is I can continue to implement the provided functions. One would assume that this would make the interface harder and more combersome to consume but if anything the resulting interface was easier to use due to forcing me to improve the methods for inspection and consumption.

16 tag values isn’t strictly necessary. In fact, it doesn’t even cover all of my own needs. The last

value type indicates “Other”, which indicates that the value points to a OtherData struct that

contains some of the types that weren’t quite important enough:

#[repr(u64)] #[derive(Copy, Clone, Debug, PartialEq, Eq, Hash)] pub enum ValueType { Undefined = 0, Null = 1, Boolean = 2, Character = 3, Number = 4, String = 5, Symbol = 6, Vector = 7, ByteVector = 8, Syntax = 9, Closure = 10, Record = 11, Condition = 12, Pair = 13, HashTable = 14, Other = 15, } #[derive(Clone, Trace)] #[repr(align(16))] pub enum OtherData { CapturedEnv(CapturedEnv), Transformer(Transformer), Future(Future), RecordType(RecordType), UserData(Arc<dyn std::any::Any>), }

Basically I chose the values to be in the ValueType based on the following criteria:

All the others aren’t that important in my opinion and don’t have to be so rigorously optimized.

This optimization was also quite good, and now we’re in a much more reasonable distance from Guile:

Running benches/fib.rs (target/release/deps/fib-0573da11404b7b6a)

fib 10000 time: [12.925 ms 13.259 ms 13.601 ms]

change: [-32.368% -26.494% -19.814%] (p = 0.00 < 0.05)

Performance has improved.

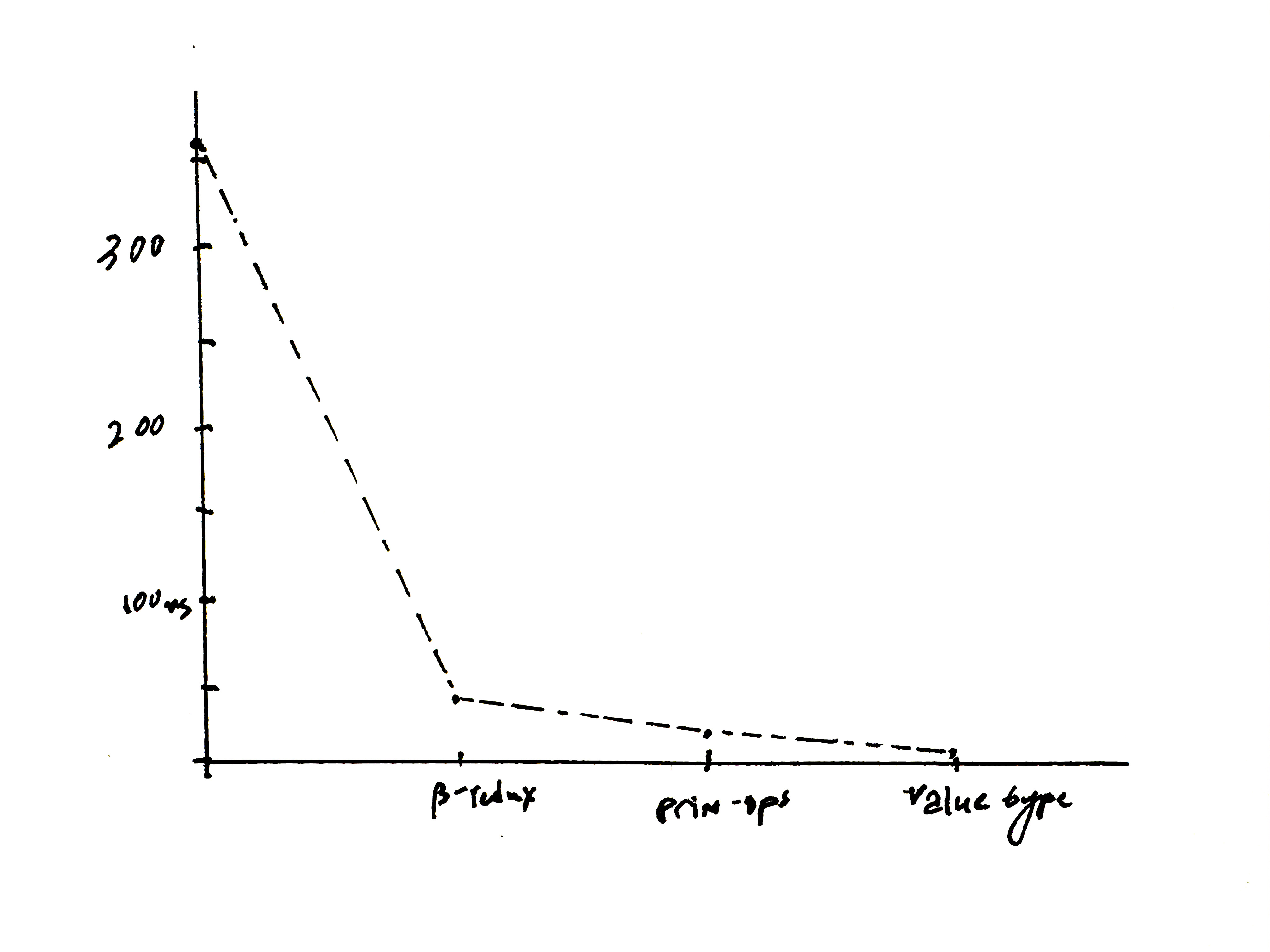

scheme_rs remains pretty slow, but each optimization gets us closer and closer to the dream

of instantaneous execution. Although I fear an asymptote, as illustrated by this graph5:

By far the best optimization was beta-reduction, which makes sense to me: it was the one that most heavily utilized the intermediate representation to produce better output. As we went away from general optimizations and to more specific runtime-oriented optimizations, we got closer to benchmark gaming.

I’d like to spend some more time improving the CPS output and also improving the SSA codegen. Some optimizations come to mind include eta-conversion, which could similarly improve the CPS output.

The fun part about programming language implementation is there’s always a new angle you can take for optimizing. As we saw here, improving basically every layer of the compiler from the CPS output to the runtime yielded positive performance improvements.

Thankfully I was able to implement some features interspersed with these optimizations, so not a lot of feature development was interrupted. Over the course of these optimizations I implemented better error handling and reporting, exception handlers and dynamic wind.

I would like to point towards the word “thought” in the previous paragraph; this was simply the conclusion I came to and we will have to decide at the end of this article if the decision was “right” or “wrong”.

Why LLVM SSA and not anything else, perhaps something more lightweight? Probably should have but I’m holding out hope I can use LLVM to make my output much faster in the long run. Also I stan Vikram Adve. Best teacher I’ve ever had.

I call these the Matt Might way and the Andrew Appel way, respectively.

This is a joke, obviously